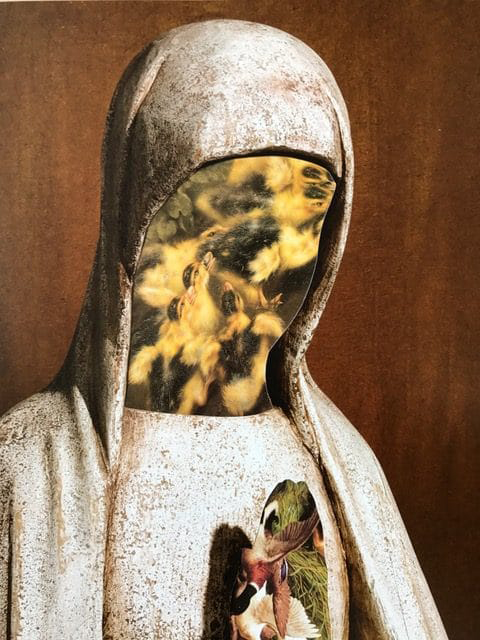

OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE BIRDS (2017)

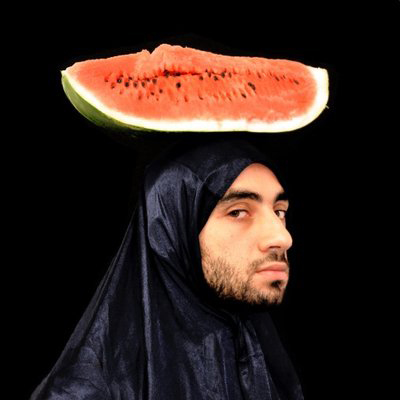

The figure of the virgin appears over and over again in this exhibition and recalls Catholic and well as Islamic iconography. Mehdi-Georges Lahlou goes about entangling codes and origins to produce hybrid icons.

In Conference of the birds, the face of the Madonna is replaced by birds. The title, taken from a Persian poem of the same name written in the 12th century by Farid Al-Din Attar, symbolically recounts the journey of the soul in search of the divine, through the fable of thirty thousand birds in search of a king. Their journey is strewn with pitfalls and the birds are plagued by doubts and hesitations. Few reach their final destination.

Marie Papazoglou

When we observe the body of work realized to date by Mehdi-Georges Lahlou, three constant principles emerge, among others: the first concerns his relationship to the body, and the second is his relationship to space. We can even say that quite often the two are intertwined. His rapport to the body is obviously not removed from his formative training as a dancer, just as the one with space is linked to his work as a “sculptor.” This term is probably the most adequate to describe his artistic approach, even including his photography— and here we touch on the third point: the question of memory—which is never absent.

Body, space and memory form a kind of trilogy, and there are at least two of these components present in each performance, sculpture or image produced by the artist. All contribute, each in their own way, to a convoluted evocation of cultural references, religious beliefs or social attributes. For him, the concern is to revisit all of them from the perspective of critical practices and the various processes that characterize contemporary art. One function of this art is to perpetually question certain taboos and beliefs of our societies, whether they be moral, religious, philosophical, political, social, cultural or aesthetic.

One could almost claim that the ambiguity of the results that Mehdi-Georges Lahlou leads us to is inversely proportional to the means he uses, means which are all relatively traditional for an artist of the 21st century at the crossroads of cultures, genres, styles and techniques. From time immemorial, in fact, artists have also practiced self-portraiture and sculpture; stained glass has lived through the centuries; and photography, ever since its origin in 1839, has constantly been used by artists, whether they are painters or not.

So from where does Mehdi-Georges Lahlou get his aptitude for producing ambiguous works from elements that are not themselves ambiguous? One cannot speak of Surrealism in his approach, but rather of an ability to dissociate all kinds of referents and sources in order to amalgamate new forms of thought. We see, therefore, the artist more as an alchemist affecting the images, materials, and media in order to establish new perceptions of them, namely the transformation of their identity, by producing objects or figures that are not categorisable due to their multireferentiality.

From this point of view, the busts with duplicate faces and the cubic Kaaba-shaped structures refer to different aspects of art history (self-portraiture, minimalism) whose codes of representation are then hijacked and redirected. It is also concerned with combining the works, either by multiplying them (72 Vierges – 2012), or by uniting them. The artist thus creates new works from older ones, placing them in a balance that is as improbable as it is evocative (Équilibre a la Kaaba – 2013), or even playing with the effects of inclusion, as in Home sweet home (2009-2010), a minimalist structure of the Kaaba with one side turned into a video screen. The whole could be summed up by the title of another skillful installation piece, paradoxically called Construction cubique, ou de la pensée confuse (2011).

It is by catapulting between these different forms and figures, while remaining inconspicuous—be it only initially—, that the artist manages to develop a particular universe. It is his own, but everyone has the right to appropriate it for him or her-self, insofar as its components are not foreign to us. On the contrary, they could almost seem familiar. The viewer has only to recompose the puzzle while attempting to unravel the sprawling thoughts of the artist.

Born in 1983 in Les Sables d’Olonne (FR)

Lives and works in Brussels, Athens and Casablanca