マラケシュにて、アフリカ写真界は独自の道へ

Leila Alaoui, Khamlia, Sud du Maroc #1, 2014, from the series The Moroccans

© Fondation Leila Alaoui

A new museum in Morocco becomes a destination for contemporary art.

モロッコに美術館が新設。現代美術のホットスポットになれるか。

By Sean O’Toole

The life and work of Leila Alaoui, the celebrated Moroccan documentary photographer, looms large over Marrakech’s newest art institution. Alaoui, who at age thirty-three was shot and killed during an al-Qaeda attack in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, was a close friend of Othman Lazraq, the photography-enthused president of the Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL), a privately owned art foundation on the southeastern outskirts of this walled city at the foothills of the Atlas Mountains. MACAAL’s inaugural photography exhibition, Africa Is No Island, bears the subtle imprint of Alaoui’s influence.

Speaking during a weekend of festivities in late February that included a boutique edition of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair to mark the international launch of MACAAL, Lazraq cited his friendship with Paris-born Alaoui, an accomplished editorial photographer and portraitist who grew up in Marrakech, for sparking his interest in photography. The two met in New York, where Alaoui studied photography, and quickly struck up a friendship. Lazraq’s first photography purchase was a work by Alaoui, who also guided him on his early acquisitions—Lazraq’s home in Casablanca includes works by Araki, Peter Beard, Malick Sidibé, and the emerging South African Phumzile Khanyile.

Africa Is No Island. Installation at Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden. Photograph by Saad Alami

“I was very young, only twenty, when I started buying photography with Leila,” said Lazraq, twenty-nine, who, like his father—Alami Lazraq, a Moroccan property tycoon and one of Africa’s wealthiest businessmen—is an architect by training. Speaking with characteristic brio, MACAAL’s youthful leader told an audience at the museum’s opening how Alaoui introduced him to her motivating ideas as a portraitist, of “facing” the real and “fixing a moment of history.” Alaoui’s sway, however, extends even further: she introduced Lazraq to Jeanne Mercier and Baptiste de Ville d’Avray, of the photography platform Afrique in Visu, who MACAAL later invited to curate Africa Is No Island.

The exhibition features a total of twenty-two individual photographers and one collective, many from the African continent, others—like Paris-based Italian photographer Nicola Lo Calzo and New Jersey-born Ayana V. Jackson—deeply occupied by its social life and connectedness to the wider world. Fittingly, the exhibition includes an image by Alaoui: a life-size portrait of a young Gnawa woman in violet-colored Mauritanian dress, photographed in 2014 in southern Morocco. Installed in an alcove with two speakers playing ambient sounds recorded in Marrakech by Italian artist Anna Raimondo, the work is excerpted from Alaoui’s The Moroccans (2010–14), a roaming project descriptive of the country’s disappearing cultural traditions and diverse racial makeup.

“We chose someone who doesn’t look like a Moroccan,” said Mercier during a walkthrough of the exhibition in reference to Alaoui’s striking portrait. Although Moroccan, the swaddled Gnawa woman’s ancestry is linked to enslaved West Africans brought to the region by Arab and Berber traffickers. Africa Is No Island is mindful of the historical forces that have wracked the African continent. The exhibition includes five portraits from Lo Calzo’s ambitious multicountry project Cham (2007–16), about the embodied legacy of the African slave trade. In 2015, New Yorker critic Hilton Als praised Lo Calzo for bringing “disappeared bodies” back to life “by their living and breathing descendants.” Aalaoui’s portrait achieves much the same.

The team of Afrique in Visu invited French curator Madeleine de Colnet to assist them in their selections, with Lazraq offering additional input—notably a prohibition on wall captions and texts for the individual works on show. “I am really driven by emotions,” said Lazraq about his philosophy as a collector and curator. The lack of explanatory texts at MACAAL is nonetheless a hindrance, especially given the preponderance of documentary and conceptually applied photography on offer. For instance, French Moroccan photographer Mustapha Azeroual’s interest in uniqueness and preindustrial modes of photography—explored in Arbre #2 (2011), a ceiling-hung installation of two hundred porcelain plates featuring one-off images of trees made with a gum bichromate printing process—is hardly self-evident.

Roughly half the work gathered in Africa Is No Island is drawn from MACAAL’s private collection, the balance sourced through Afrique in Visu’s vast network, which is visually signaled at the ground-floor entrance to the exhibition in a wall-scale collage of photographs featured on the platform’s website and exhibitions. Africa Is No Island properly begins with three color images by Beninese photographer Ishola Akpo, from his series L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux (Essence is invisible to the eye, 2014), matter-of-fact descriptions of dowry objects—like an enamel plate and bottle of gin—that belonged to his recently deceased grandmother. The gently melancholic note registered by this work recurs throughout Africa Is No Island, even in the photographs of Walid Layadi-Marfouk and Lebohang Kganye, the show’s youngest exhibitors.

Along with Alaoui and Hicham Gardaf—a Tangier-born photographer whose series The Red Square (2014–17) offers an economical insight into Morocco’s rapid urban development in a style redolent of Lewis Baltz and Angolan photographer Edson Chagas—Layadi-Marfouk represents the vanguard of young Moroccan photography. His Riad series (2017–ongoing) is largely set in his family home in Marrakech and portrays his kin, notably an aunt, involved in choreographed actions. An outlier in the series, Haya Jat (Starfixion), presents this aunt in a blue evening gown, arms outstretched, facing an audience of two from the stage of Marrakech’s Le Colisée, an Art Deco cinema acquired by the Layadi family in 1971.

“The idea of the series came when I moved to the US,” said Layadi-Marfouk, who studied math at Princeton before changing to photography. “The visual representation [in the US] of my culture was completely separate and other from the way I had internalized, sublimed, and fantasized it growing up in Morocco. They were just black-and-white images of violent submission, pain, and extremism.”

Similar to Layadi-Marfouk, South African–born Kganye also uses portraiture to affirm her identity and explore intergenerational relations in her breakout 2013 series, Ke Lefa Laka (My heritage). Kganye’s photographic tableaux, which effortlessly blur the line between playful fantasy and sober document, present her in comical poses wearing her grandmother’s clothes and interacting with figures and settings photocopied from various family albums gathered during a research trip in 2012. “Photographs are more than just a memory of moments passed, or people no more, or a reassurance of an existence,” noted Kganye when she first exhibited her work at the Market Photo Workshop, Johannesburg, in 2013, adding that they were also evidence of “a constructed life.”

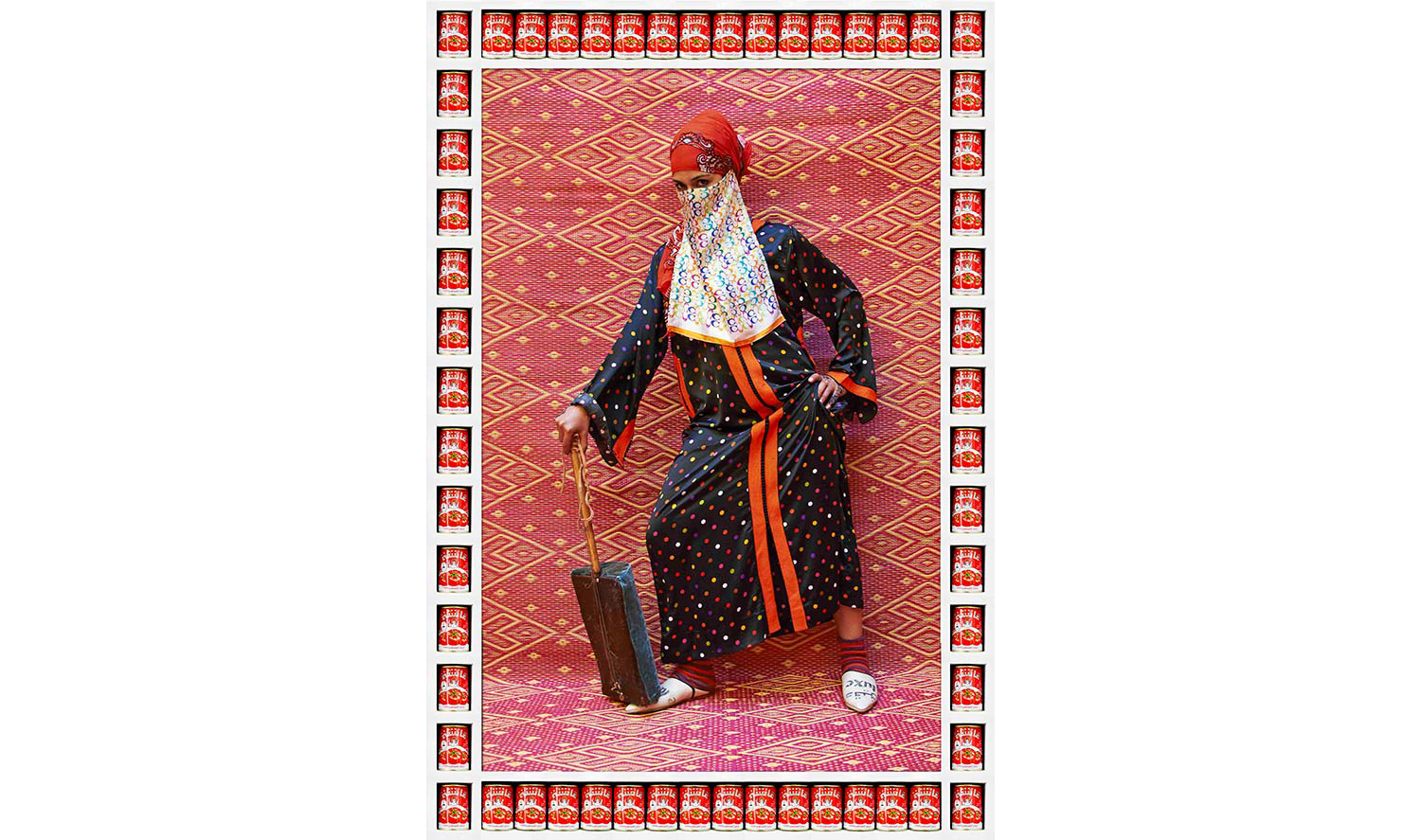

Fun also remains essential to the work of Hassan Hajjaj, a Moroccan pop artist who took up photography in 1989. Best known for his vivid and playfully garish street portraits of Moroccan youth, Hajjaj’s photography is a flip, urban counterpoint to Alaoui’s respectful portraits, and is on permanent view at Riad Yima, a boutique and tearoom in the medina that also includes a gallery. As part of the festivities around MACAAL’s opening, Hajjaj invited Yoriyas Yassine Alaoui to exhibit his street photographs of ball players, sunbathers, and worshippers from the series Casablanca Not the Movie (2015–ongoing).

Hajjaj’s initiative lent a biennial-like feel to the weekend of MACAAL’s opening, as did writer and translator Omar Berrada’s thoughtfully curated program of talks on the subject of decolonization at the fair, including a fascinating performance-lecture by the Black Athena Collective (photographers Dawit L. Petros and Heba Y. Amin) on pharaonic-era trade along the Red Sea.

Hassan Hajjaj, Marmouche, 2012 Courtesy the artist

In recent years, Marrakech has emerged as an important art destination in North Africa. This legacy is partly founded on the successes of the Marrakech Biennale, an unapologetically progressive showcase of Mediterranean—rather than exclusively African—art, founded in 2005. The 2009 edition, for instance, included a picnic hosted by Tangier-based photographer and artist Yto Barrada, and British artist Shezad Dawood’s Make It Big (Blow Up), hoax stills from a Pakistani remake of Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow–Up (1966). However, the withdrawal of sponsorship last year led to the cancellation of the 2018 biennial, which would have coincided with MACAAL’s opening.

Private collectors like the Lazraq family and Nabil El Mallouki, whose Museum of Art and Culture of Marrakech opened in early 2016, offer an alternative approach to sponsor-led events like the biennial. These new private museums also slot into a growing network of cultural venues in Marrakech: some are modest, like the photography museum and Hajjaj’s Riad Yima; others—like the Yves Saint Laurent Museum, opened last year opposite a garden that was created by artist Jacques Majorelle and later acquired by the late French fashion designer—cater to Marrakech’s new class of culture tourists.

“The role of a museum is to engage and educate people, to somehow bring a small touch of light and hope,” said Lazraq before proudly ushering journalists into Africa Is No Island. “I think Morocco needs it, Africa needs it, we all need it.” Part of that education, he added, involves reframing perceptions of photography. Lazraq jovially recalled his father’s befuddlement at his preference for photography, video, and installation art, saying he enjoyed the pushback. It helped reinforce a central article of faith: “Photography is a medium I love and care for.” The eccentricities characterizing MACAAL’s debut photography exhibition design and approach to information notwithstanding, Africa Is No Island is a confident expression of Lazraq’s passion for the medium and ebullient vision to make his North African museum a destination for photography enthusiasts.

An Insight Into Moroccan Pop Art

It is commonly admitted that pop art is a reflection of urban environment and mass media. Pop artists succeeded in revealing the hidden beauty and aesthetics of daily and forgotten objects.

Campbells’ soup cans or Coca Cola bottles had never been iconic before Andy Warhol’s work immortalized them using acrylic. For a long time, this movement has been considered as a critic of the consumer society and its representatives drew their inspiration directly from the American popular culture. But what if artists with different sensitivity, background and culture gave birth to a new similar style? What would it look like if “exotic” products were transformed into new symbolic icons?

Few days ago, the 2014 PULSE Prize was given to the native moroccan Hassan Hajjaj. Kathy Basttista (Director of Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art NY), Paddy Johson (founder and Editorial director of Art F City) as well as other musuems’ directors and curators succumbed to the satiric mood and kitsch composition of the My Rock Stars portrait series. As you can imagine, this international recognition increased the artist’s popularity and he is currently one of the most followed contemporary artists.

After leaving Larache, his native city at a young age, he moved with his family to London. He now navitgates between England and Marrakech when he is not invited to an exhibition opening somewhere. Permanently travelling between East and West, Hassan Hajjaj has been immersed into a variety of influences which contributed to building his multicultural bias. This explains the birth of his astonishing artistic work that celebrates both modernity and tradition. Hajjaj’s photography, collages, designs and installations are indeed an ode to beautiful and expressive fusion between his Moroccan origins and European culture. Moreover, this incredible self-taught artist is not afraid of materials and is a master of different genres. Making recycled furniture, album-coverage pictures or ready-to-wear dresses; his creations are diverse but his know-how is unique. Indeed, the master word that describes well all what his hands put into form is originality.

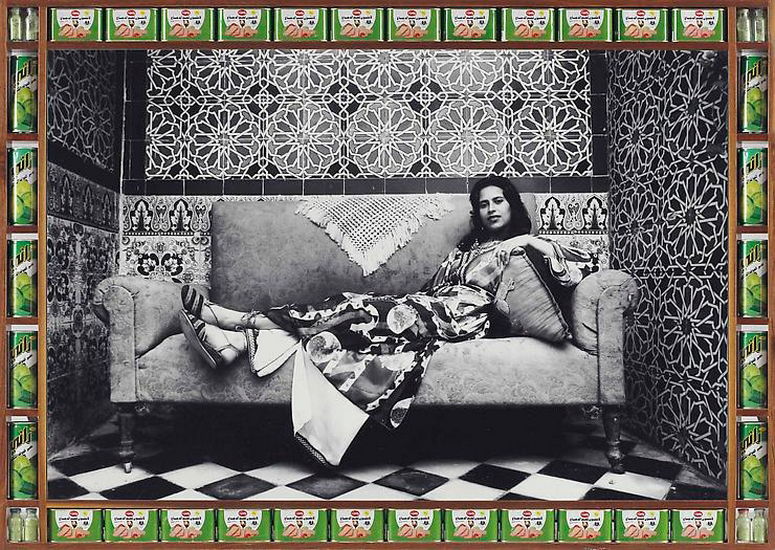

But, each time I have the pleasure to stare at his work I can’t help thinking of Andy Warhol’s universe. Actually, a number of art critics draw this same parallelism and I’m going to develop further why I see this comparaison as relevant. When you have a glance at Hajjaj’s portraits, you can easily distinguish two parts. The frame and the picture. Both are an expression of the colorful and highly dynamic world of Hajjaj that is highly influenced by his North African roots. If we focus on the frame composition, we can notice the use of the serigraphy technic, a direct heritage of the pop-art movement. Yet, the objects are really used in a repeated way to compose the frame and are not only drawn. Sometimes, the frame can also use some fabrics like painted straw (that popular Moroccan families use as a mat) or be just painted in acrylic (that was also often used by Warhol as a material that symbolizes the industrial world, since acrylic is used for painting cars).

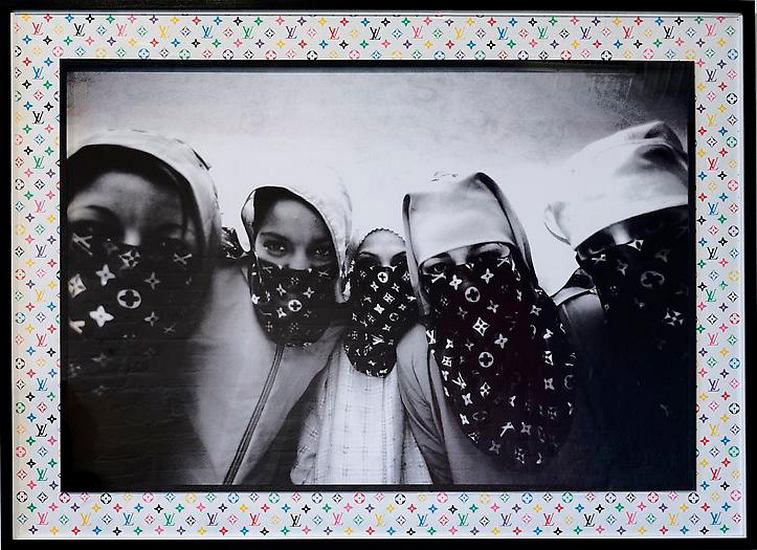

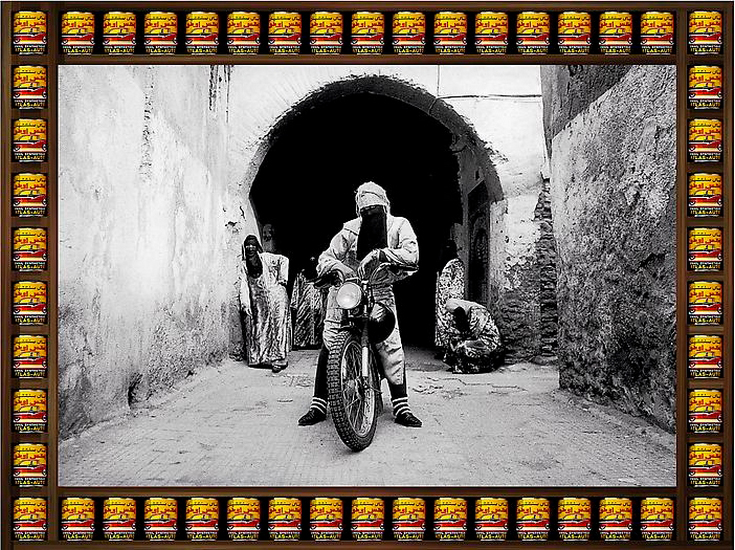

Aicha’s tomato cans and other Moroccan grocery products replace the Heinz, Kellogs and Brillo packaging. This mention to the advertisement industry appears to be an ironic vision of our society and the use of repetition trivializes the object. While Warhol started his artistic path in the advertisement world and worked for magazines like Vogue and Glamour, surprisingly enough Hajjaj started in the fashion world as well. First as a retailer, he was able to anticipate trends and his shop quickly became the epicenter of London’s street-style. He then started working with stylists and up to now, he features his own clothing designs in his photographs. It is all the more funny since a large number of his pictures show luxury brand logos on fake items. This kind of products (Jellaba with Louis Vuitton sign, or a Gucci babouch/slippers) do actually exist on the moroccan souk-market, but when Hajjaj uses them on his vivid patterns, you can notice them better and appreciate his subtle sense of humour. When you see all his trendy niqabs and hijabs you actually forget about all the stereotypes about these islamic items and focus more on the image itself.

Hajjaj said himself that the pattern printing worked like a camouflage and started to use all the permanent in-and-out fashion motifs in the west (animal-prints, polka dots, camo…) on traditional long dresses mocking in that way all kind of stereotypes. As for his visual language, his images are definitely full of power and catchy bright colors (another fact that makes me think about Warhol). Red and green are for example very predominant in his last series of portraits of young moroccan women who move in the city of Marrakech on their motorcycles. According to me, the flowers, the Arabic characters, the mosaics and the different geometric forms that are mixed in the scenes makes the viewer feel an incredible energy. This energy is nothing but the current ‘joie de vivre’ of all these authentic women of their time that wear local Islamic fashion but have a daring character and a modern state-of-mind.

Thus, each time I see a Hajjaj portrait I can only smile and feel more alive. As far as I’m concerned, the details of its photographs remind me the warmth, the noise and the smells of the old medina. A bit of street-style and a HipHop background are the ingredients of Hajjaj’s job that challenges excellently the outdated cliché that people might have about Morocco and the Islamic world in general.

In a nutshell, Hassan Hajjaj’s work appears to be a continuity of the pop-art movement. It is true that the artist claims his independence saying that he is “a big fan of Warhol but he never tried to emulate him. » He adds » I just do what comes naturally and it’s a big compliment to be compared to him.” But I personally see his work as an extension of Warhol’s work with a Moroccan -« Dghmira » -sauce. The chosen themes and objects, use of serigraphy and bright colors as well as the ironic vision of society prove the strong similarity between these two incredibly talented and inspiring artists: Andy Warhol and Hassan Hajjaj. This makes him one of the best representatives of the current booming in the cultural boiling Arab urban scene that finds its influences in a tradition smartly adapted to the contemporary world.

HASSAN HAJJAJ|ハッサン・ハジャジ

1961年、モロッコ王国北部の港町アライシュ出身。12歳の時にロンドンへ移住した経験から、東洋と西洋のイメージを融合し、両者の最高のものを引き出すことをめざす。彼の被写体は友人やアーティスト、または街角の他人であり、彼らの持つエネルギーを切り取った作品は明るく大胆で、生命力にあふれている。インスタレーションや彫刻、パフォーマンスなども手がけ、現在はモロッコとロンドンを行き来しながら世界各地で活躍中。